Folklore in Film is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

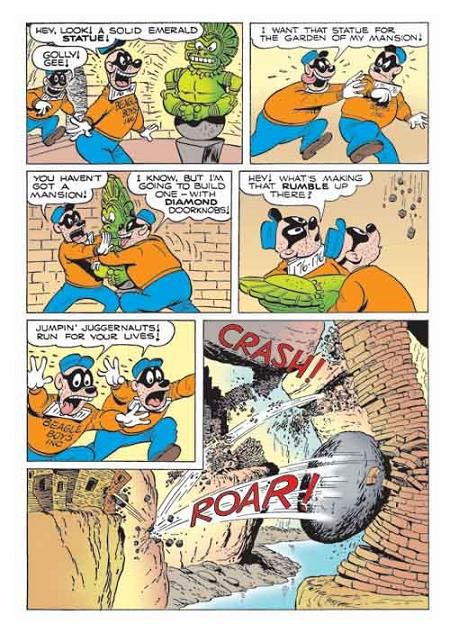

Did you know the opening sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark was based on a Scrooge McDuck comic?

No, seriously.

The booby trapped idol…

The boulder roll…

Those were lifted from the story “The Seven Cities of Cibola,” which was published in 1954 in issue 7 of the Uncle Scrooge comic.

That comic book story, in turn, was inspired by Colonial Mexican folklore dating back to at least the 16th century.

Tales of the “seven cities of gold”—collectively known as Cíbola—inspired actual expeditions by Spaniards into what is now New Mexico.

The most famous of those expeditions being the one launched by conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado in 1540.

Coronado explored the Southwest and Midwest for two years.

He became the first European to see the Grand Canyon.

And, if we treat The Last Crusade as historically accurate, he left behind a golden cross.

But, spoiler alert: Coronado never found a golden city.

Anyway, George Lucas and Lawrence Kasdan, who were responsible for Raiders of the Lost Ark’s story and screenplay respectively, decided to set the action of their booby-trapped temple sequence in South America, trading Cíbola for the Temple of the Chachapoyan Warriors.

Which as far as I can tell has no basis in folklore.

Yes, there was a Chachapoyan culture, based in the cloud forests of the Peruvian Andes.

And Chachapoyas were great builders, as evidenced by the walled settlement Kuélap.

Buuut they didn’t build bobby trapped temples.

Nor did they make a sacred, golden Chachapoyan Fertility Idol like the one in the film.

The Chachapoyan Fertility Idol vs. the Dumbarton Oaks Birthing Figure

In fact, that film prop was based on the very real (but not necessarily authentic) Dumbarton Oaks birthing figure.

Go ahead and tell me in the comments, based on this picture:

Is this a genuine, pre-Columbian Aztec artwork representing the sex goddess Tlazolteotl a.k.a. Ixcuina of Aztec mythology?

Or is it a 19th-century European forgery, betrayed both by its craftsmanship and its exaggerated, “savage” style, which is atypical of actual pre-Columbian Aztec art but in line with contemporary European perceptions of what such art would’ve looked like?

Look, even if the Dumbarton Oaks birthing figure is authentic, the film’s golden version of the idol is in the wrong place.

Why didn’t Lucas and Kasdan just set their temple in Mexico?

Why’d they put it on Chachapoyan land in South America?

Turns out there was a very good reason for that.

I’ll explain.

Pssst. You can watch a video adaptation of this essay right here. Text continues below.

I’ll also explain how Harrison Ford’s Indiana Jones spoils the plot of Raiders fifteen minutes into the movie.

And I’ll do a heck of a lot of explaining about the Ark of the Covenant and whether or not there’s a Biblical (or folklorical) basis for it being capable of melting faces.

Which I’m sure is top of mind for everybody.

Vikings in South America? Dr. René Belloq vs. Jacques de Mahieu

On my most recent rewatch of the 1981 Stephen Spielberg-directed classic, one character in particular really stood out to me:

Indiana’s arch archaeological nemesis, Dr. René Belloq.

Now, I’ve seen Raiders at least twenty times.

I had the Indiana Jones trilogy on VHS as a kid.

But I don’t think I ever quite appreciated the effort the filmmakers and actor Paul Freeman put into making Belloq a somewhat nuanced villain.

Don’t get me wrong, he’s still a huge scumbag.

But at least he’s a self-aware scumbag, responding to Indy’s “Too bad the Hovitos don’t know you the way I do, Belloq,” line, with the confessional:

“Yes, too bad.”

And, of course, later we get this gem from Belloq, which in my opinion is simultaneously beautiful aaand a bit on the nose:

“I am a shadowy reflection of you. It would take only a nudge to make you like me, to push you out of the light.”

But what I didn’t know about Belloq, before doing research for this video, is that he was based on a real person:

The French anthropologist and Nazi collaborator Jacques de Mahieu.

De Mahieu infamously theorized that the Vikings had brought civilization to South America.

As evidence of this, he pointed to Pedro de Cieza de Leon’s 16th-century description of the Chachapoyas as the ”whitest and most handsome of all the people that I have seen in Indies.”

But as I explored in an essay/video on a similar topic, Did the Ancient Celts Reach the Americas Before the Vikings?, the concept of “white” as a race didn’t exist in the pre-Columbian Americas.

So when colonial accounts talk about certain aboriginal peoples having “white” skin, the implication isn’t that they look like Europeans, it’s simply that they have a lighter skin tone compared to other aboriginal peoples.

As a white supremacist piece of sh*t, however, De Mahieu really wanted to push the narrative that those people in Peru building those awesome structures all those hundreds of years ago must have had help from Europeans.

He went so far as to mischaracterize an account given by the chronicler/conquistador Pedro Pizarro, claiming Pizarro wrote that the Chachapoyas had blond hair.

When in fact, Pizarro never wrote that.

All this being said, I like from a narrative and world-building perspective how Lucas and Kasdan had a historical basis for putting a Nazi-callobrating French archeologist in Chachapoyan territory.

This was a real place of interest for Belloq’s historical counterpart.

Even if the scene in question was inspired by Scrooge McDuck, and by extension, Mexican folklore.

Just don’t tell Dr. Jones about the folklore part, because as we find out in the very next scene, the classroom scene, he is not a fan of folklore.

Indiana Jones Hates Folklore (And Loves Spoiling Movies)

And I quote:

“This site also demonstrates one of the great dangers of archaeology. Not to life and limb, although that does sometimes take place. No, I’m talking about folklore.”

The irony, of course, is that the film—and the entire Indiana Jones franchise, for that matter—is premised on Indy finding folkloric artifacts.

He’ll be skeptical of an artifact’s existence and/or supernatural characteristics in Act I.

But by Act III he’ll have proven it exists and borne witness to its power.

In the classroom scene, Indy actually foreshadows how folklore will lead him to the location of the Ark of the Covenant.

As a kid, I never really paid attention to this part. I just assumed the stuff he says in class was archeology professor white noise.

But when you actually listen…

“In this case local tradition held that there was a golden coffin buried at the site. And this accounts for the holes dug all over the barrow and the generally poor condition of the find. However, chamber three was undisturbed.”

No, he’s not talking about the Ark. But a “golden coffin” is a pretty decent description of what the Ark ends up looking like.

What’s more, when Indy gets to Egypt, he sees people digging up the desert. Holes all over the place. As an archeologist, he must have been aghast at the poor condition of the site.

Alas, there is still one chamber that is undisturbed. And that’s where Indy finds the Ark.

Fifteen minutes in, we’ve got a rough outline of what’s going to happen.

What’s Coming Out of That Ark?

Then in the next scene, when Indy is visited by the Army Intelligence guys, we get a whole bunch of exposition that fills in the details.

And if you pay close attention, you’ll see the big reveal of what’s going to come out of the Ark is effectively spoiled.

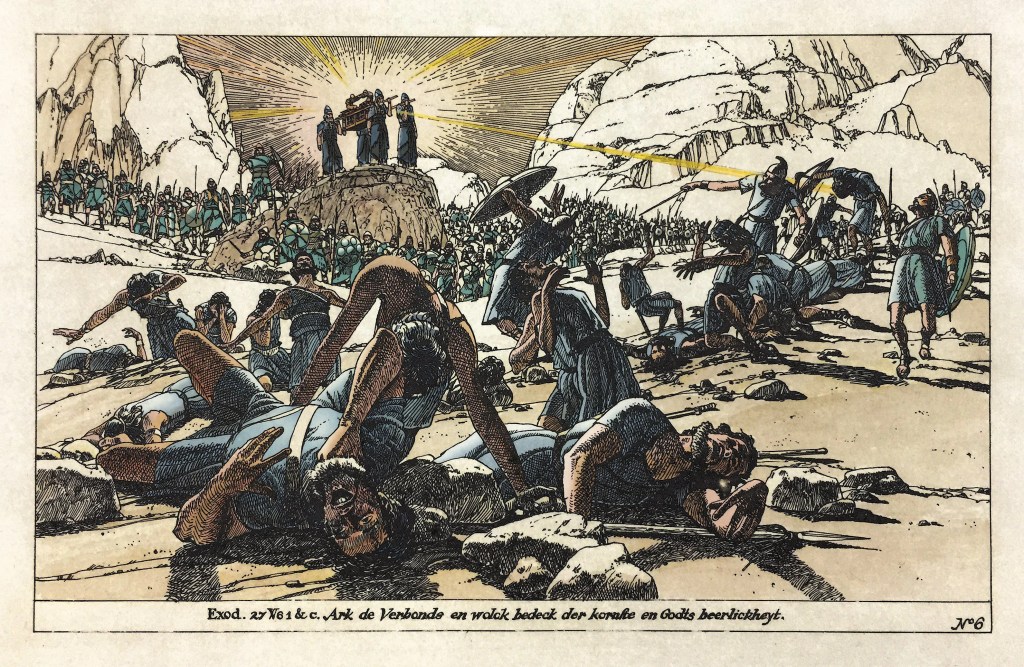

Remember when they’re looking at that illustration in the book?

On of the Army intelligence guys asks:

“What’s that supposed to be coming out of there?”

And Indian Jones replies:

“Who knows… lightning… fire… the power of God.”

Turns out, yeah: that’s exactly what comes out of there.

You could’ve just left it at “who knows?”

And if you’re wondering where that illustration even came from:

Ralph McQuarrie made it.

He’s the dude who famously did a lot of the foundational concept art for the original Star Wars trilogy.

Apparently, McQuarrie used a traditional printing plate to give the image that antiquated look.

But if the plot-spoiling illustration is just a prop, is there any actual evidence, in art or literature, of the Ark being able to do what it does in the film?

The answer is…sort of.

The Book of Samuel from the Hebrew Bible is our most important source here.

In the Old Testament, this is split into two books. And it is in First Samuel, chapter 6, where we find an account of the Philistines returning the Ark to the Israelites after they had stolen it.

To quote verse 19:

“But God struck down some of the inhabitants of Beth Shemesh, putting seventy of them to death because they looked into the ark of the LORD. The people mourned because of the heavy blow the LORD had dealt them.”

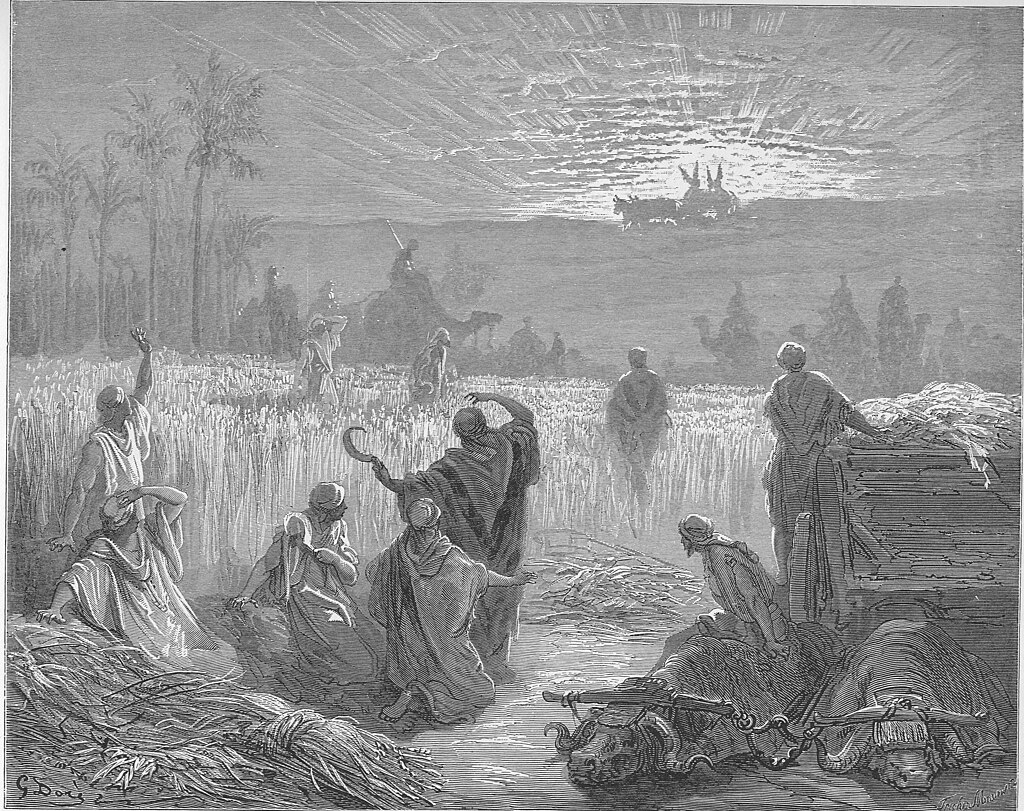

The French artist Gustave Doré made an engraving in 1866 depicting the ark’s return to Beth Shemesh.

And, as you can see, there are some striking similarities here to McQuarrie’s prop print and to what we see onscreen in that infamous scene.

I think American painter Benjamin West’s “Joshua passing the River Jordan with the Ark of the Covenant” from the year 1800 might have helped inspire that visual as well.

Granted, that painting refers to a story from the Book of Joshua, specifically chapter 3, verses 14 through 17, which sees the River Jordan stop flowing when the priests carrying the Ark step into it.

But really, we’ve only scratched the surface of the Ark’s power.

The True Power of the Ark (And Why Indiana Jones Won’t Touch It)

In Second Samuel, chapter 6, verses 6 and 7, we learn about this poor fella Uzzah who tries to save the Ark from falling, but in the process makes the mistake of touching it.

Here’s what happens next:

“The Lord’s anger burned against Uzzah because of his irreverent act; therefore God struck him down, and he died there beside the ark of God.”

Uhhh, not cool, God. Not cool.

Clearly, Indy is aware of this story, hence his insistence that he and John Rhys-Davies’ Sallah not touch the Ark and that they carry it with those poles.

Back in First Samuel 5:1–5, the Philistines stick the stolen Ark in front of a big statue of their god Dagon and the statue keeps falling over face-first.

Which may have inspired Indiana Jones’ toppling of that big Anubis statue in the Well of Souls.

Then, starting in First Samuel 5:6, God sends the Philistines a plague and they break out in tumors (or hemorrhoids, depending on the translation) and that’s when the Philistines decide, alright, we better give this Ark back.

It is in the Talmudic literature, however, i.e. in the commentaries and analyses of rabbis and Torah scholars, where we find the good stuff.

Like the idea that the Ark of the Covenant can fly or hover.

To quote Sotah 35a:

“[T]he Ark carried its bearers in the air and crossed the Jordan.”

Then there’s the idea that those two golden cherubim set on either end of the Ark can shoot out sparks and kill animals and light plants on fire.

To quote the Midrash Tanhuma, Vayakhel 7:1:

“Two sparks issued from between the cherubim that killed the snakes and scorpions and burned the thorns. The smoke rose up from it in a straight column.”

I mean, come on. The column?

And it gets better, because even those energy tendrils we see in the film have a basis in the Midrash, specifically Sifra, Shemini, Mekhilta DeMiluim II, in which the deaths of Aaron’s two sons are described as follows:

“What was their death like? Two strands of fire came forth from the holy of holies and parted into four. Two entered the nostrils of one, and two, the nostrils of the other, burning their bodies and leaving their garments intact.”

The holy of holies, FYI, is the structure that houses the Ark of the Covenant.

It definitely seems like Lucas and Kasdan did their homework here.

The spectacle of the Ark being opened in the film aligns pretty closely with what we find in the literature.

Switching back to the Bible, the New Testament this time, we find more potential Raiders inspiration in Revelation 11:19.

And I quote:

“Then God’s temple in heaven was opened, and the ark of his covenant was seen within his temple, and there were flashes of lightning, rumblings, peals of thunder, an earthquake, and heavy hail.”

Cool.

Can the Ark of the Covenant Really Melt People’s Faces?

As for the face-melting, that doesn’t really have a basis in the literature.

Although there are a couple of Old Testament examples that come close.

Like Leviticus 9:24, when we are told “Fire came out from the Lord and consumed the burnt offering and the fat on the altar, and when all the people saw it, they shouted and fell on their faces.”

Why did they fall on their faces?

Because their faces were melting?

Probably not, but still.

Then, in Zechariah 14:12, we get:

“This is the plague with which the LORD will strike all the nations that fought against Jerusalem: Their flesh will rot while they are still standing on their feet, their eyes will rot in their sockets, and their tongues will rot in their mouths.”

Lovely.

Did the Egyptian Pharaoh Shishak (Shoshenq) Really Steal the Ark?

But enough about the Ark itself:

What about the guy who allegedly took it, the Egyptian pharaoh Shishak, and the place he allegedly took it to, Tanis?

Is any of that rooted in Judeo-Christian mythology or local folklore?

Or did Lucas and Kasdan just make it up?

Welp, for starters, the pharaoh Shishak is a character in the Hebrew Bible.

He famously sacks Jerusalem and then, as noted in Frist Kings 14:26, “he took away the treasures of the house of the Lord and the treasures of the king’s house; he took everything.”

The implication being that the Ark of the Covenant was included in that everything. And Shishak took it back to Egypt.

Now, Shishak is identified with a historical Egyptian pharaoh, Shoshenq, who founded the Twenty-second Dynasty of Egypt in the 10th century BCE.

Buuut there is no Egyptian account of Shoshenq having raided or conquered Jerusalem.

On Shoshenq’s Karnak list, which is a record of the 150+ places he (supposedly) conquered during his 926 BCE military campaign into the Levant, there are cities north and south of Jerusalem, such as Megiddo and Sharuhen respectively, but not Jerusalem itself.

It’s as if he deliberately avoided the area.

Theories abound as to whether Shoshenq was paid a tribute to leave Jerusalem alone; or if the cities near Jerusalem on his list were just copy and pasted (so to speak) from previous pharaohs and he was never actually in the area at all.

Or maybe Shoshenq did conquer Jerusalem in the 10th century BCE and it did get recorded but then the Egyptians erased it from their records…for some reason.

Perhaps to hide the fact that they were now in possession of the world’s most powerful weapon / stone tablet receptacle?

Why Is the Ark Found in the “Lost City” of Tanis?

Okay, let’s run with this theory for a second.

Or, at minimum, let’s just assume Shoshenq did conquer Jerusalem and he did claim the Ark of the Covenant as a prize.

Would he have brought it to Tanis? (Which is a real Egyptian city in the Nile Delta about 100 miles north and east of Cairo.)

And the answer is:

Yeah, Shoshenq probably would have brought the Ark there because during his reign, Tanis was Egypt’s capital city.

It was never a lost city, mind you. It didn’t get swallowed up by a sandstorm.

Excavations of its many tombs and temples began in the 19th century.

The tombs of Shoshenq II and Shoshenq III were discovered there.

Where is Shoshenq I’s tomb?

Not at Tanis, apparently. His final resting place has yet to be discovered.

As for the Well of Souls…

The Well of Souls From Raiders Explained: Fact or Folklore?

Look, there is a real Well of Souls but it’s in Jerusalem on the Temple Mount inside the Dome of the Rock.

And while Crusaders equated this spot with the Holy of Holies, believing it once held the Ark, most scholars believe the Holy of Holies would have been located above the Well of Souls, where the Foundation Stone is now.

Regardless, it’s not in Tanis.

And, no snakes.

In the movie, one of the defining characteristics of the fictional Well of Souls is…it’s full of snakes. Including one very camera-ready cobra.

Believe it or not, the idea of an ancient vault in Tanis having a serpentine defense system isn’t that far-fetched.

Are Tombs in Tanis Really Full of Snakes? (Sort Of!)

Symbolic depictions of rearing cobras, known as uraei, adorn many of the funerary items discovered in Tanis.

The most famous examples were found in the tomb of Psusennes I and include a silver coffin, a golden death mask, and a pectoral.

These rearing cobras, or uraei, are likely representations of the Egyptian goddess Wadjet, who, in ancient Egyptian mythology, is the patron deity and protector of Lower Egypt.

Upper Egypt, meanwhile, falls under the protection of the vulture goddess Nekhbet.

Hence, the winged cobra became a symbol of a united Lower and Upper Egypt.

A Solar Disk with a Serpentine Twist? “The Headpiece to the Staff of Ra” Explained

As for that bronze medallion with the crystal in the middle, i.e., the Headpiece to the Staff of Ra…yeah, that’s totally made up.

But it is interesting, to me, anyway, that the cobra goddess Wadjet has a connection to Ra.

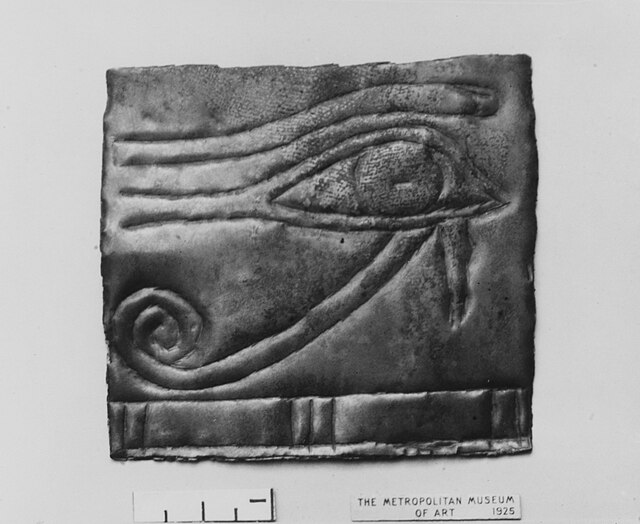

Know this symbol?

That’s a wedjat-eye, a representation of the Eye of Ra.

Which can also be depicted as a solar disk, with a uraeus or two on the sides.

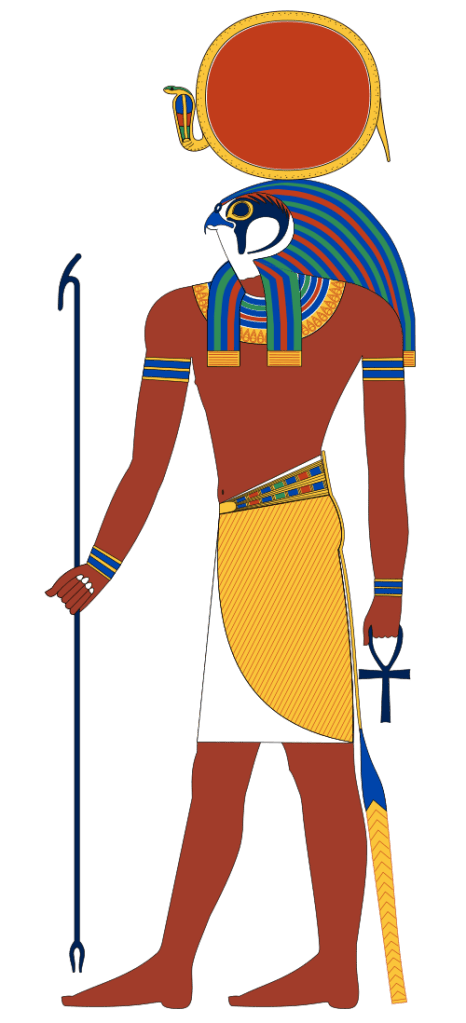

Like this one, on Ra’s head.

And if we just combine the bird and the solar disk, we get the Headpiece to the Staff of Ra.

Minus the snake.

Sorry, Indy hates snakes.

Of course, the headpiece isn’t just some fancy bit of decor; it’s functional.

It focuses sunlight and turns into a fiery beam.

This phenomenon couldn’t possibly be connected to Wadjet and and the Eye of Ra and cobras—

Oh, wait, yeah, it could be.

As American Egyptologist Robert K. Ritner explained in the Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, “fire-spitting serpents” were employed as perimeter guardians in ancient Egypt, both in artwork and in rituals.

“Such a role is in fact stereotypical for uraei, and is codified in the architectural feature known as the ‘cobra frieze’ which commonly appears atop walls, shrines, baldachinos, etc. As personal guardians, bands of uraei may ring the crown or modius of deities and rulers, at once the analogue of encircling serpent and fiery radiance. In all such cases, the function of the uraeus hearkens back to its well-known origin as the ‘fiery eye’ of the sun god sent forth against the god’s enemies, whether human, divine, or…demonic.”

No, there’s not a perfect parallel there.

The fiery eye of Egyptian mythology is invoked for protection and/or vegeance—not for highlighting spots on three-dimensional maps.

But still, the symbolism is there.

Final Thought: Raiders Gets an “A” for Folklorical Accuracy

And overall, when we look at how Raiders of the Lost Ark engages with folklore and mythology throughout its run time, I think it’s admirable how accurate a lot of it is—despite Lucas intentionally setting out to create an homage to “lowbrow” pulp adventures from the 1930s.

A lot of people care about the historical accuracy of films.

I’m here for the folklorical accuracy.

And Raiders… gets an A.

Not that I do ratings on this channel.

Should I do ratings on this channel?

Like give a grade for folklorical accuracy at the end of each essay/video?

Let me know in the comments.

Thanks for reading.

Fan of folk horror?

You might be interested in my short film Samhain, available over on the Irish Myths channel.

More the reading type?

Check out…

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

Samhain in Your Pocket

Perhaps the most important holiday on the ancient Celtic calendar, Samhain marks the end of summer and the beginning of a new pastoral year. It is a liminal time—a time when the forces of light and darkness, warmth and cold, growth and blight, are in conflict. A time when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is at its thinnest. A time when all manner of spirits and demons are wont to cross over from the Celtic Otherworld. Learn more…

Irish Monsters in Your Pocket

In the Ireland of myth and legend, “spooky season” is every season. Spirits roam the countryside, hovering above the bogs. Werewolves lope through forests under full moons. Dragons lurk beneath the waves. Granted, there’s no denying that Samhain (Halloween’s Celtic predecessor) tends to bring out some of the island’s biggest, baddest monsters. Prepare yourself for (educational) encounters with Irish cryptids, demons, ghouls, goblins, and other supernatural beings. Learn more…

Leave a comment