Folklore in Film is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn a small affiliate commission.

Hold onto your skulls.

We’re charging head-first into Tim Burton’s Sleepy Hollow.

This 1999 film is equal parts campy and creepy.

With the infamous Headless Horseman serving up many of its stylized scares.

And while you likely already know that the screenplay was adapted from Washington Irving’s 1820 short story, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker really did a full overhaul of the plot.

And changed all of the characters.

Notably, the headless horseman, who, in the short story is a mysterious and rarely-seen spectre, is reimagined as an unstoppable killing machine with a very specific, supernatural origin story.

But does the film’s depiction of the character actually hue closer to what we find in headless horseman lore?

Because before Irving ever put pen or quill to paper, multiple headless horsemen (and at least one headless horsewoman) could be found clip-clopping their way through German folklore, Arthurian legend, Irish folklore, and beyond.

I’m I. E. Kneverday. Let’s take a look.

Pssst. You can watch a video adaptation of this essay right here. Text continues below.

Bringing Sleepy Hollow to Life: From Story to Cartoon to Film

Regardless of how you feel about the original Washington Irving short story, I think we can all agree that it would take a film to really bring his famous, fictionalized version of Sleepy Hollow (which is a real place, FYI) to life.

No, I’m not talking about Burton’s film.

I am of course talking about the animated short—narrated by Bing Crosby—that came out half a century earlier.

It was part of the anthology The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad.

Burton took the visual language established in that animated film and carried it over into the live-action affair.

And yet Sleepy Hollow is more than just a remake or a retelling of an old tale.

To reach its 1 hour and 45 minute runtime, character backstories had to be elaborated on and subplots had to be developed.

Long story short:

Everyone’s a witch.

Christina Ricci’s Katrina Van Tassel is a witch.

Miranda Richardson’s Lady Mary Van Tassel is a witch.

So is her twin sister the Crone Witch.

That one was pretty obvious.

And the tortured Ichabod Crane played by Johnny Depp is revealed to be the son of a witch who was literally tortured.

None of this is in Irving’s original text.

But there are some witch-related passages.

For example, Irving wrote that Ichabod Crane was a “perfect master of Cotton Mather’s “History of New England Witchcraft,” in which, by the way, he most firmly and potently believed.”

Cotton Mather was a Puritan clergyman who had a hand in the Salem Witch Trials (which I discuss in more detail in my video/essay on Robert Eggers’s film, The VVitch).

And while “History of New England Witchcraft” isn’t the title of an actual book, it’s likely a reference to a pair of books Mather wrote on the subject:

1689’s Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions and 1692’s Wonders of the Invisible World.

Irving also wrote how Ichabod would “pass long winter evenings with the old Dutch wives… and listen to their marvellous tales of… the headless horseman, or Galloping Hessian of the Hollow, as they sometimes called him. He would delight them equally by his anecdotes of witchcraft.”

Two things:

First, in the movie, Constable Ichabod Crane is a vocal proponent of modern scientific methods.

His character arc then sees him embrace or at least acknowledge that in his universe there is for sure some supernatural stuff going on.

Whereas in the short story, he’s a nerdy teacher who already believes wholeheartedly in the supernatural and is thus an easy target for the village mischief-maker, Brom Bones.

Which leads me to…

Second, clearly the decision was made to take the witchcraft tidbits from the short story and not only expand upon them but present them as reality.

In Irving’s Sleepy Hollow, the identity of the horseman is left ambiguous.

The fate of Ichabod Crane is left ambiguous.

Brom Bones gets the girl.

And it’s never actually established that anything supernatural goes on whatsoever.

Or that anyone has been killed by a horseman, supernatural or otherwise.

Which leads us back to our main question:

Did Hollywood take Irving’s “favorite spectre of Sleepy Hollow” and turn him into a bloodthirsty, supernatural killer?

Or did Irving take a bloodthirsty supernatural killer from folklore and turn him into this non-lethal spectre?

Hans Jagenteufel: German Folklore’s Headless Horseman

Behold, Exhibit A:

The German folktale of Hans Jagenteufel.

Whose surname translates to Devil-Hunter.

He wears a long grey cloak, rides a grey horse, he’s booted, he’s spurred, he has a bugle, and he carries his severed head.

So you can imagine how scared that woman from Dresden must have been back in 1644 when this German headless horseman caught her gathering acorns in the woods.

Instead of drawing a weapon, Hans Jagenteufel questions her.

Pretty sternly.

It’s a pretty stern questioning.

And the woman’s like, “No, the foresters (i.e., the people who manage the forest) are okay with me doing this.

“I’m poor and they look kindly on the poor.”

And so Hans Jagenteufel has this existential crisis.

He talks about he’s been doing this headless horseman thing for about 130 years now.

He talks about his relationship with his dad.

I should’ve listened to you, pop.

And he explains how he was “condemned to wander about the world as an evil spirit” in part because he wasn’t kind to the poor.

Now, neither iteration of Sleepy Hollow’s headless horseman ever speaks, let alone sits down for a free therapy session with an acorn lady.

But in the short story, Irving wrote that “the most authentic historians of those parts” believe that their local horseman is an undead Hessian soldier who, every night, rides from the cemetery to the battlefield in search of his head, which had been carried away by a cannonball during the American revolution.

And while this headless horseman origin story is presented as a theory, it’s still interesting to see that quintessential ghost story plot point embedded within it:

A restless spirit having unfinished business.

The Hans Jagenteufel story adheres to this basic structure as well.

And similarly presents the headless horseman as a nonviolent, tortured soul.

The film, meanwhile, opts for a more complex (some might say convoluted) backstory for its headless horseman.

He’s revealed to be under the control of Lady Van Tassel.

She had watched him die in the woods as a girl.

And made a deal with Satan.

So Lady Van Tassel becomes this middle manager.

And the horseman is her underling, attacking only at her command.

Which sounds sort of familiar.

Where else have I seen a witch summoning a headless horseman?

The Green Knight: Headless Horseman of Arthurian Legend

Oh, right:

2021’s The Green Knight.

In which Morgan Le Fay, the famed enchantress of Arthurian legend, works her magic to raise the titular knight from his tomb in the Green Chapel.

He rides into King Arthur’s court on his horse carrying a big old ax and challenges the knights there to a beheading contest.

You take a swing, I take a swing.

Sir Gawain does the deed.

Then the Green Knight calmly retrieves his severed head and tells Sir Gawain to meet him in a year so he can return the blow.

And yes, it’s the same story (literally) in the 14th-century chivalric romance Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Which is what writer/director David Lowery based his screenplay on.

And look, maybe Sleepy Hollow’s screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker was familiar with this Arthurian legend too—it was a popular one well before Lowery’s film.

While it isn’t a beat-for-beat copy, the big reveals are identical:

A secret sorceress was controlling a horseman so she could complete an evil plot.

Heck, maybe Washington Irving read Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and that’s how he got the idea for his headless horseman in the first place.

Although, according to many online sources (we’ll get into ‘em), The Green Knight wasn’t Irving’s primary influence for his Headless Hessian.

Instead, we have the Irish headless horseman The Dullahan to thank.

The Dullahan: Irish Folklore’s Headless Horseman

To quote The Irish Place:

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow in America is based on this Irish legend.”

To quote The Irish Times:

“The most famous and lasting iteration of the Dullahan figure must be the headless horseman featured in Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

And to quote Books Are Our Superpower:

“The earliest ‘Headless Horseman’ figure that can be identified is the Dullahan.”

Now, I don’t want to say all of those quotes I just read to you are garbage.

So I’ll just say I think they overstate things a bit.

For starters, I can’t find any medieval Irish texts that document the dour deeds of the Dullahan.

He seems to be a more recent invention.

One of the earliest printed references to the Dullahan occurs in the Irish antiquarian Thomas Crofton Croker’s 1825 book Fairy Legends and Traditions of the South of Ireland.

Which, fun fact, was later translated into German by the Brothers Grimm.

Anyway, according to Croker, the Dullahan drives:

“The Death Coach or Headless Coach and Horses, [which] is called in Ireland ‘Coach a bower;’ and its appearance is generally regarded as a sign of death, or an omen of some misfortune.”

Irish poet W.B. Yeats built upon Croker’s characterization in his 1888 book, Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry, pairing the Dullahan with another famed figure associated with impending death from Irish folklore.

And I quote:

“An omen that sometimes accompanies the banshee is the coach-a-bower (cóiste bodhar) – an immense black coach, mounted by a coffin, and drawn by headless horses driven by a Dullahan.

“It will go rumbling to your door, and if you open it, according to Croker, a basin of blood will be thrown in your face.

“These headless phantoms are found elsewhere than in Ireland.

“In Norway the heads of corpses were cut off to make their ghosts feeble.

“Thus came into existence the Dullahans …

For anyone who’s seen the 1959 Disney classic(?) Darby O’Gill and the Little People, you’ll know that this is how the Dullahan is presented there.

Minus the blood in the face.

And the headless horses.

Look it’s the Disney version of the Dullahan I’d say it’s actually pretty scary considering.

Comparing this headless horseman to Sleepy Hollow’s, and The Green Knight’s, it is noteworthy that again we see not a witch but close enough teaming up with a horseman.

Not necessarily controlling him though, but clearly working with him.

The Dullahans of Wales, Scotland, and Cornwall

We find figures similar in nature to the Irish Dullahan across the pond in Wales, Scotland, and Cornwall—all so-called Celtic nations, I might add.

The Welsh Dullahan equivalent stands out for being one of the few supernaturally imbued headless women in folklore.

Her name is “Fenyw [venyoo] heb un [in] pen,” which, appropriately enough, means “the headless woman.”

And she rides “Ceffyl heb un pen,” — “the headless horse.”

Galloping our way up to Scotland, an 1826 issue of the Glasgow Chronicle reported that “visions” had been seen of “carts, caravans, and coaches, going up Gleniffer braes without horses, with horses without heads.”

Given that Washington Irving’s father was from Scotland, it’s possible that the senior Irving shared this headless folklore with his son.

However, it’s equally possible that young Washington got the idea for his headless horseman from his mother, who was from Cornwall.

The Cornish Dullahan is a headless coachman who operates on a yearly cycle, pulling into the courtyard of The Molesworth Arms hotel every New Year’s Eve.

And since the hotel opened way back in the 16th-century (it started out a coaching inn) it’s possible Irving’s mother would have been familiar with the tale.

The headless coachman remaking the same journey over and over does bear some resemblance to Sleepy Hollow’s headless horseman going back and forth from the battlefield to the cemetery.

Granted, the time scales are different: yearly vs. nightly.

And of course the New Year’s Eve arrival date is significant given that that’s the day the aforementioned Green Knight arrives in Camelot to challenge the knights of King Arthur’s court to the beheading game.

It could be a coincidence.

Cú Roi: The Green Knight’s Irish Progenitor

It could be The Green Knight inspired all of these folkloric figures—including the Irish Dullahan.

But lest you think I’m taking legendary character creation accolades away from the Irish and giving them to the British, it should be noted that the Green Knight of Arthurian legend was based on the king/wizard Cú Roí from Irish mythology.

I did a whole video/essay on it over on my Irish Myths channel.

I’m not gonna spend any more time on it here because…

I don’t think Irving was directly influenced by any of those headless horsemen or horsewomen or headless coachmen I just mentioned.

A Headless Hessian in White Plains, New York

And that’s because history tells us there was once a real headless Hessian soldier in Irving’s neck of the woods (all puns intended).

To quote the November 1st, 1776 entry of The Revolutionary War Memoirs of Major General William Heath:

“A shot from the American cannon at this place [White Plains] took off the head of a Hessian artillery man.”

White Plains, New York, FYI, is located less than ten miles from Tarrytown, home of Washington Irving and the setting of his famous tale.

(The village of Sleepy Hollow was originally incorporated as North Tarrytown.)

Great Scott! Did the Wild Huntsman Inspire Sleepy Hollow’s Horseman?

History also tells us that in 1817, just a couple years prior to beginning work on his Legend, Irving befriended the Scottish poet and novelist Walter Scott, who had famously translated the German poem Der Wilde Jäger (The Wild Huntsman).

A poem about a not-so-nice hunter who is doomed to be hounded forever by the devil and the “dogs of hell” as punishment for his crimes.

(Sound familiar?)

A poem that was inspired by Norse mythology.

Where you can find the all-father Odin leading the so-called wild hunt.

So there you have it:

Irving took one scoop of local Revolutionary War lore about a headless Hessian.

Added a dash of his mentor’s mythical Germanic musings.

And voila:

You have Irving’s headless horseman.

The cursed spirit.

Forever riding through the night.

Quite a different character, it turns out, from Burton’s murderous, mind-controlled headless horseman.

Who, as we’ve seen, has more in common with The Green Knight of Arthurian Legend than the Wild Hunter of Germanic tradition.

But what do you think?

Let me know which iteration of the headless horseman you prefer in the comments below.

Thanks for reading.

Fan of folk horror?

You might be interested in my short film Samhain, available over on the Irish Myths channel.

More the reading type?

Check out…

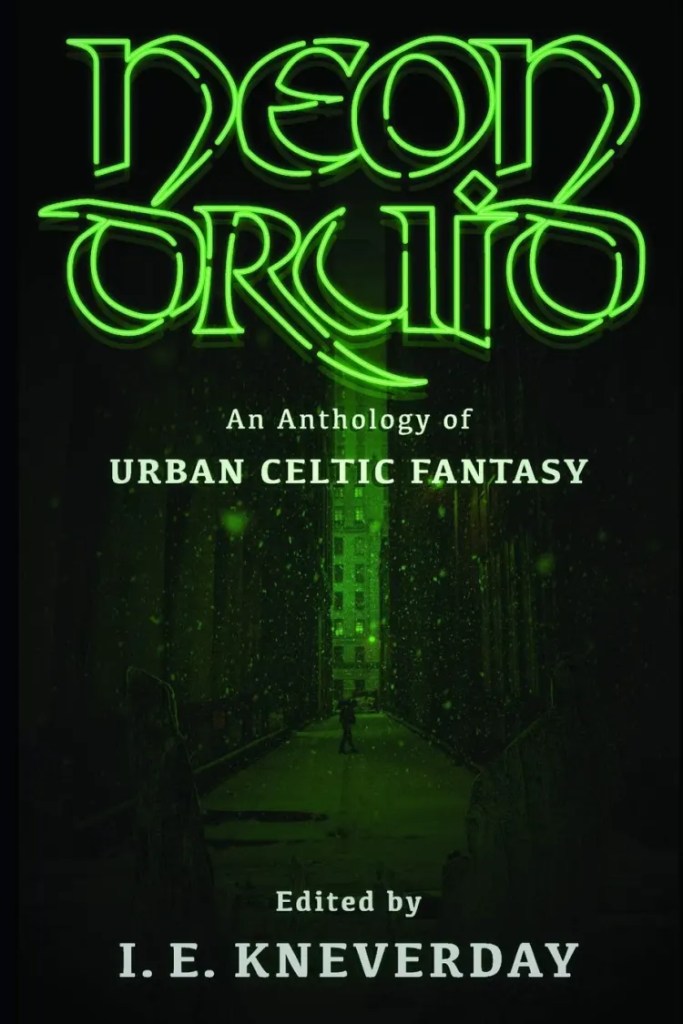

Neon Druid: An Anthology of Urban Celtic Fantasy

“A thrilling romp through pubs, mythology, and alleyways. NEON DRUID is such a fun, pulpy anthology of stories that embody Celtic fantasy and myth,” (Pyles of Books). Cross over into a world where the mischievous gods, goddesses, monsters, and heroes of Celtic mythology live among us, intermingling with unsuspecting mortals and stirring up mayhem in cities and towns on both sides of the Atlantic, from Limerick and Edinburgh to Montreal and Boston. Learn more…

Leave a comment